Last December I spent 5 days surviving on the Philippine island where Hiroo Onoda hid during three decades, believing that the Second World War hadn’t yet finished. This story reminds us very much of that of Ho Van Lang and father in the Vietnamese jungle.

Hiroo Onoda – a Japanese official who fought for the Empire –was sent to Lubang Island in 1944, around the end of the war. The orders for his men and himself were never to surrender, get behind the enemy lines, carry out sabotage operations and survive on their own until they received new orders.

After the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 when the Japanese surrendered, Onoda and two of his companions carried on fighting, hidden in the jungle and convinced that the war had not finished.

The Philippine army – which spent two decades trying to catch these three men – managed to kill two of them so Onoda spent the last years living alone.

During three decades Onoda survived on what he could find in the jungle, shooting cattle and robbing the few courageous natives who dared to go near the island’s mountains.

There were several Japanese expeditions that went in search of him, but Onoda – who suffered a pathologic distrust – mistook them for enemy spies. Over the years pamphlets were launched from aeroplanes as well as other efforts, but none succeeded in convincing him that the imperial army had been defeated.

His paranoid obsessions reached such an extreme that when his brother came from Japan to convince him he ignored him, thinking him a traitor who had sold himself to the enemy.

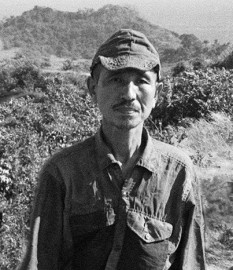

It wasn’t until he was visited by his ex-commandant in March, 1974 that Onoda ended his absurd personal war. Being relieved of his mission by the commander who had assigned it to him 30 years before was the only reason this man eventually gave in. He was then 52 years old and had wasted half his life.

Although the whole of Japan received Onoda as a war hero, I personally never liked this character who made life impossible for the island’s inhabitants and who destroyed dozens of families.

During my stay in Lubang I was able to gather together the testimonies of different people whose relatives had been killed by Onoda. Many of these crimes were carried out with malice. Despite the fact that he, theoretically, carried out these crimes in name of his Emperor, Onoda was a vicious person who had a deep contempt for the island’s natives.

For 30 years Onoda didn’t live, but neither did he let live. Three decades wasted fighting against a non-existent enemy. His day to day was a great ordeal: he slept little, lived in constant alert and was always on the move from one side of the jungle to the other. This has nothing in common with other stories of castaways where it’s always possible to find some kind of romanticism however desperate their experiences.

Although his survival feat impresses, my esteem and admiration for this castaway is no way as high as for others who existed in the past. For this reason I have never attempted to meet him in Tokyo whilst there, and Onoda was still alive only three years ago.

This year I will publish a complete article on my experience on Lubang Island. Meanwhile you can follow us on Facebook.

{ 0 comments… add one now }